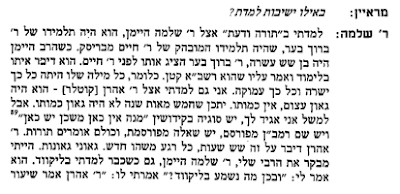

Harav Hagaon Yehuda Wagshal Shlita

Dovid Hamelech declares, in Tehillim, that he had one request of Hakadosh Baruch Hu: אַחַת שָׁאַלְתִּי מֵאֵת ה' אוֹתָהּ אֲבַקֵּשׁ שִׁבְתִּי בְּבֵית ה' כָּל יְמֵי חַיַּי לַחֲזוֹת בְּנֹעַם ה' וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ. This request begins with Dovid asking that he dwell in the beis Hashem his entire life, and concludes with him asking: וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ.

What does the word וּלְבַקֵּר mean? It is commonly translated as “to visit,” which would mean that Dovid was asking to dwell in the beis Hashem his entire life and visit His heichal. But this is an inherent contradiction: Is he a permanent resident in Hashem’s house or is he a visitor?

It is very possible that “visit” is not actually the correct translation of וּלְבַקֵּר. Some meforshim say that this word is related to boker (morning), meaning that Dovid Hamelech not only wants to dwell in the beis Hashem, but he wants to arrive there early in the morning — in other words, he also wants to be on time.

Others explain that וּלְבַקֵּר connotes inspection, as in bikur mumin. The halachah is that before you bring a korban, you examine it for a few days to make sure there’s no disqualifying blemish; this is known as bikur mumin. Dovid Hamelech was saying, “I want, first of all, to dwell in Hashem’s house, and I also want וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ — to be there in the heichal, examining what needs to be fixed and checking what is missing. And I want to be the one to fix it.”

This is the true meaning of the term bikur cholim as well. People typically think of bikur cholim as a mitzvah to visit the sick, but in truth the mitzvah is fulfilled when a person goes to the patient and checks what he needs: Does he need the visitor to clean something? Does he need medication? Does he need a doctor? Just as bikur cholim means checking what the patient’s needs are and trying to supply those needs, when Dovid Hamelech asked וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ, he meant that he did not want to visit the heichal as a guest, but rather in order to examine what needs to be fixed there and to be the one who is zocheh to fix it. Why did Dovid Hamelech daven that he be the one to fix what needs repair? If the need to fix something would present itself to him, then he would certainly do it, but why daven for that? Furthermore, according to this understanding of וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ, it sounds as though Dovid Hamelech actually made two requests of Hashem: to dwell in His house his whole life, and also to be the one who checks what needs fixing and repairs it. If so, that is not one request, but two — so how could he say אַחַת שָׁאַלְתִּי?

Perhaps we can explain that Dovid Hamelech’s one request was really שִׁבְתִּי בְּבֵית ה’ כָּל יְמֵי חַיַּי — to be a permanent member of Hashem’s house and reap the full benefits of being there. Dovid Hamelech understood that if he would just come to the beis Hashem and benefit from everything it had to offer, that would not suffice, because in order to properly connect to something, it’s not enough to be a receiver — you also have to be a giver, too, and contribute something. Accordingly, when he said: אַחַת שָׁאַלְתִּי מֵאֵת ה', I have one request of Hashem, he was referring to the request of שִׁבְתִּי בְּבֵית ה’ כָּל יְמֵי חַיַּי. But how would he ensure that his connection was real? Only if he also had the opportunity to contribute, as he declared: וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ.

We can suggest that this idea is reflected in this week’s parashah as well, in the Torah’s account of how the daughters of Tzelafchad endeavored to obtain a portion in Eretz Yisrael. When Hakadosh Baruch Hu said that every male in Klal Yisrael would be zocheh to a portion in Eretz Yisrael, which would then be passed down throughout the generations, the daughters of Tzelafchad realized that their father would be left out, as he was no longer alive and he had no sons to inherit his portion. It had not been said explicitly that daughters would get a portion in Eretz Yisrael in such a case, so daughters of Tzelafchad came to Moshe Rabbeinu and complained.

What was their objection? Simply understood, they were saying that it was not fair that everyone else would be receiving a share of Eretz Yisrael and they would not. But Rashi, citing Chazal, explains that they did not merely want real estate.

When the Torah describes how they presented their case to Moshe Rabbeinu, it delineates their entire lineage, tracing all the way back to Yosef: וַתִּקְרַבְנָה בְּנוֹת צְלָפְחָד בֶּן חֵפֶר בֶּן גִּלְעָד בֶּן מָכִיר בֶּן מְנַשֶּׁה לְמִשְׁפְּחֹת מְנַשֶּׁה בֶן יוֹסֵף. Why, asks Rashi, does the Torah give their lineage all the way back to Yosef? To inform us that their desire for a portion in Eretz Yisrael traced back to Yosef; just as he cherished Eretz Yisrael, as he made the shevatim promise to take his bones from Mitzrayim and bury him there, his descendants, the daughters of Tzelafchad, cherished Eretz Yisrael as well, and that is why they approached Moshe Rabbeinu asking for a portion in Eretz Yisrael.

Rashi is conveying that the daughters of Tzelafchad were not interested merely in owning land in Eretz Yisrael as a financial asset; the reason they were asking for a portion of the land was that they cherished Eretz Yisrael.

We can ask, however, why it was so important to the daughters of Tzelafchad to receive a portion in Eretz Yisrael. Even had they not been granted a portion, they wouldn’t have been left behind in Mitzrayim, or in the desert — they would have entered Eretz Yisrael regardless! So if they really loved Eretz Yisrael and had no interest other than chibas haaretz, why did they care who owned the land? As long as they were in Eretz Yisrael, the kedushah of living in the land should have been enough for them!

We can explain this using the idea expressed by Dovid Hamelech. The daughters of Tzelafchad knew that if they would come to Eretz Yisrael without owning a part of it, then even if they would gain a great deal from Eretz Yisrael’s holy environment, they would be limited to the role of receivers. Since they would not own any part of the land, they would have nothing to contribute. Those who owned portions in Eretz Yisrael would have to be moser nefesh to settle the land and perform the mitzvos hateluyos baaretz, thereby contributing to Eretz Yisrael. But if they were to enter the land without having a yerushah in it, they would be coming as guests and outsiders, who could enjoy the benefits of the land, but could not give to it. Because they valued Eretz Yisrael, it was not enough for them just to take from it— they wanted to be able to contribute to the land, and thereby connect with it in a real way. To do that, they needed to have a portion in it.

We learn a very important lesson from the way the daughters of Tzelafchad related to Eretz Yisrael, and from the way Dovid Hamelech related to the beis Hashem: We can connect to spiritual matters by taking and benefiting from they have to offer, but if we really want to have a part in them, we also need to give and contribute to them in some way. Let’s not just look only for the שִׁבְתִּי בְּבֵית ה’ — let’s also constantly emphasize and look for the ways to accomplish וּלְבַקֵּר בְּהֵיכָלוֹ.