An article from Rabbi Y.Y. Jacobson.

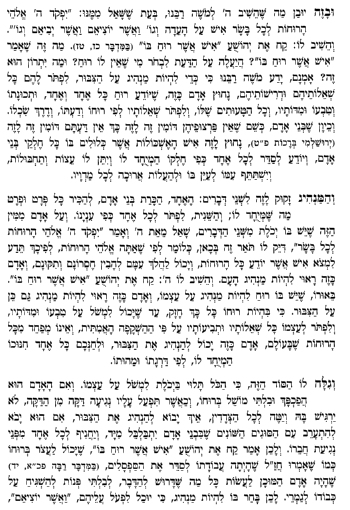

It is a baffling story. The portion of Korach tells of the "Test of the Staffs" conducted when people contested Aaron's appointment to the High Priesthood. G‑d instructs Moses to take a staff from each tribe, each inscribed with the name of the tribe's leader; Aaron's name was written on the Levite Tribe's staff. The sticks were placed overnight in the Holy of Holies in the Sanctuary. When they were removed the following morning, the entire nation beheld that Aaron's staff had blossomed overnight and bore fruit, demonstrating that Aaron was G‑d's choice for High Priest.

In the words of the Torah (Numbers 16): “And on the following day Moses came to the Tent of Testimony, and behold, Aaron's staff for the house of Levi had blossomed! It gave forth blossoms, sprouted buds, and produced ripe almonds. Moses took out all the staffs from before the Lord, to the children of Israel; they saw and they took, each man his staff.”

What was the meaning of this strange miracle? G-d could have chosen many ways to demonstrate the authenticity of Aaron’s position.

What is more, three previous incidents have already proven this very truth: the swallowing of Korach and his fellow rebels who staged a revolt against Moses and Aaron; the burning of the 250 leaders who led the mutiny; and the epidemic that spread among those who accused Moses and Aaron of killing the nation. If these three miracles did not suffice, what would as fourth one possibly achieve? What then was the point and message of the blossoming stick?

One answer I heard from my teacher was this: The blossoming of the staff was meant not so much to prove who the high priest is (that was already established by three previous earth-shattering events), but rather to demonstrate what it takes to be chosen as a high priest of G-d, and to explain why it was Aaron was chosen to this position. What are the qualifications required to be a leader?

Before being severed from the tree, this staff grew, produced leaves, and was full of vitality. But now, severed from its roots, it has become dry and lifeless.

The primary quality of a Kohen Gadol, of a High Priest, of a man of G-d, is his or her ability to transform lifeless sticks into living orchards. The real leader is the person who sees the possibility for growth and life where others see stagnation and lifelessness. The Jewish leader perceives even in a dead stick the potential for rejuvenation.

How relevant this story is to our generation, especially over this past year. Following the greatest tragedy ever to have struck our people, the Holocaust, the Jewish world appeared like a lifeless staff. Mounds and mounds of ashes, the only remains of the six million, left a nation devastated to its core. An entire world went up in smoke.

What happened next will one day be told as one of the great acts of reconstruction in the history of mankind. Holocaust survivors and refugees set about rebuilding on new soil the world they had seen go up in the smoke of Auschwitz and Treblinka.

One of the remarkable individuals who spearheaded this revival was the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994), whose 27th yartzeit is this Sunday, the third of Tamuz (June 13). The Rebbe, together with other great Jewish sages and leaders from many diverse communities, refused to yield to despair. While others responded to the Holocaust by building memorials, endowing lectureships, convening conferences, and writing books – all vital and noble tributes to create memories of a tree which once lived but was now dead -- the Rebbe urged every person he could touch to bring the stick back to life: to marry and have lots of children, to rebuild Jewish life in every possible way. He built schools, communities, synagogues, Jewish centers, summer camps, and yeshivas, and encouraged and inspired countless Jews to do the same. He opened his heart to an orphaned generation, imbuing it with hope, vision, and determination. He became the most well-known address for scores of activists, rabbis, philanthropists, leaders, influential people, and laymen and women from all walks of life – giving them the confidence to reconstruct a shattered universe. He sent out emissaries to virtually every Jewish community in the world to help rekindle the Jewish smile when a titanic river of tears threatened to obliterate it.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe urged his beloved people to use the horrors of destruction as an impetus to generate the greatest Jewish renaissance and to create “re-Jew-venation.” He gazed at as dead staff and saw in it the potential for new life.

His new home, the United States, was a country that until then had dissolved Jewish identity. It was, as they used to say in those days, a “treifene medinah,” a non-kosher land. Yet the Rebbe saw the possibility of using American culture as a medium for new forms of Jewish activity, using modern means to spread Yiddishkeit. The Rebbe realized that the secularity of the modern world concealed a deep yearning for spirituality, and he knew how to address it. Where others saw the crisis of a dead staff, he saw an opportunity for a new wave of renewal and redemption.

The past year has been uniquely challenging for each of us. A lot of pain and agony have pierced the serenity of so many. Yet the Jewish people have emulated Aaron's staff: From crisis, our people have created opportunity; from darkness and loneliness, we have grown more confident, united, forgiving, and authentic.

Rabbi Yehudah Krinsky, one of the Rebbe’s secretaries, related the following episode.

“It was around 1973, when the widow of Jacques Lifschitz, the renowned sculptor, had come for a private audience with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, shortly after her husband's sudden passing.

“In the course of her meeting with the Rebbe, she mentioned that when her husband died, he was nearing completion of a massive sculpture of a phoenix in the abstract, a work commissioned by Hadassah Women's Organization for the Hadassah Hospital on Mt. Scopus, in Jerusalem.

“As an artist and sculptor in her own right, she said that she would have liked to complete her husband's work, but, she told the Rebbe, she had been advised by Jewish leaders that the phoenix is a non-Jewish symbol. It could never be placed in Jerusalem!

“I was standing near the door to the Rebbe's office that night, when he called for me and asked that I bring him the book of Job, from his bookshelf, which I did.

“The Rebbe turned to Chapter 29, verse 18, "I shall multiply my days like the Chol." “And then the Rebbe proceeded to explain to Mrs. Lifschitz the Midrashic commentary on this verse which describes the Chol as a bird that lives for a thousand years, then dies, and is later resurrected from its ashes. Clearly then, a Jewish symbol. “Mrs. Lifschitz was absolutely delighted. The project was completed soon thereafter.

In his own way, the Rebbe had brought new hope to this broken widow. And in the recurring theme of his life, he did the same for the spirit of the Jewish people, which he raised from the ashes of the Holocaust to new, invigorated life. He attempted to reenact the “miracle of the blossoming staff” every day of his life with every person he came in contact with.

A story:

Rabbi Berel Baumgarten (d. in 1978) was a Jewish educator in an orthodox religious yeshiva in Brooklyn, NY, prior to relocating to Buenos Aires. He once wrote a letter to the Rebbe asking for advice. Each Shabbos afternoon, when he would meet up with his students for a study session, one student would walk into the room smelling from cigarette smoke. Clearly, he was smoking on the Shabbos. “His influence may cause his religious class-mates to also cease keeping the Shabbos,” Rabbi Baumgarten was concerned. “Must I expel him from the school, even with the lack of clear evidence that he is violating the Shabbos?”

The Rebbe’s answer was no more than a scholarly reference: “See Avos Derabi Noson chapter 12.” That’s it.

Avos Derabi Noson is a Talmudic tractate, an addendum to the Ethics of the Fathers, composed in the 4th century CE by a Talmudic sage known as Reb Nasan Habavli (hence the name Avos Derabi Noson.) I was curious to understand the Rebbe’s response. Rabbi Baumgarten was looking for practical advice, and the Rebbe is sending him to an ancient text…

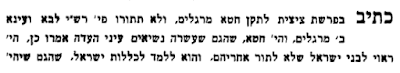

I opened an Avos Derabi Noson to that particular chapter. I found a story told there about Aaron, our very own High Priest of Israel. Aaron, the sages relate, brought back many Jews from a life of sin to a life of purity. He was the first one in Jewish history to make “baalei teshuvah,” to inspire Jews to re-embrace their heritage, faith, and inner spiritual mission. But, unlike today, during Aaron’s times to be a sinner you had to be a real no-goodnik. Because the Jews of his generation have seen G-d in His full glory; and to rebel against the Torah way of life was a sign of true betrayal and carelessness.

How then did Aaron do it? He would greet each person warmly. Even a grand sinner would be greeted by Aaron with tremendous grace and love. Aaron would embrace these so-called “Jewish sinners” with endless warmth and respect. The following day when this person would crave to sin, he would say to himself: How will I be able to look Aaron in the eyes after I commit such a serious sin? I am too ashamed. He holds me in such high moral esteem, how can I deceive him and let him down? And this person would abstain from immoral behavior.

We come here full circle: Aaron was a leader, a High Priest, because even his staff blossomed. He never gave up on the dried-out sticks. He never looked at someone and said, “This person is a lost cause, he is completely cut off from his tree, of any possibility of growth. He is dry, brittle, and lifeless.” For Aaron, even dry sticks would blossom and produce fruit.

This is the story related in Avos Derabi Noson. This was the story the Lubavitcher Rebbe wanted Rabbi Berel Baumgarten to study and internalize. Should I expel the child from school was his question; he is, Jewishly speaking, a dried-out and one tough stick!

The response of an Aaron is this: Love him even more. Embrace him with every fiber of your being, open your heart to him, cherish him and shower him with warmth and affection. Appreciate him, respect him and let him feel that you really care for him. See in him or her that which he or she may not be able to see in themselves at the moment. View him as a great human being, and you know what? He will become just that.