The Mishna Rosh Hashana (1:2) says בארבעה פרקים העולם נידון בפסח על התבואה בעצרת על פירות האילן בר"ה כל באי עולם עוברין לפניו כבני מרון שנאמר (תהלים לג, טו) היוצר יחד לבם המבין אל כל מעשיהם ובחג נידונין על המים. Why does the Mishna switch from the word נידון to the word נידונין regarding water? The Rogatchover explains based upon the Gemorah Sukkah (55b) that that the korbanos offered on Sukkos come to atone for the gentiles so that rain will come for them; they are also part of the prayer for rain. When gentiles are included, they are defined as a bunch of individuals and therefore the Mishna uses the word נידונין, plural language. In the first cases of the mishna, when it is only the avodah of Klal Yisrael, then it uses a singular language for Klal Yisrael comes together as one group. The Rogatchover understands the din of tzibbur, comprised of various individuals is only applicable to Klal Yisroel, not to gentiles. It is שבעים נפש, one נפש of the body of the nation only for בני יעקב.

The Briskor Rav understands the same way and says it as peshat in a possuk in Vaeschanan.

The Gemorah in Berachos (8a) says אמר הקב"ה: כל העוסק בתורה ובגמילות חסדים, ומתפלל עם הציבור - מעלה אני עליו כאילו פדאני לי ולבני מבין אומות העולם. Why is praying with the tzibbur equated with redemption? The Maharal (Netzach Ch. 10) explains that when the Mikdash is standing, it unites as all. It is what defines us as one unit of Klal Yisroel, one tzibbur. In golus, there is nothing to define us as a tzibbur. Even if an entire body of Jews gather together, they are separate individuals that happen to be under the same roof. What defines Klal Yisroel as a tzibbur? Praying together before Hashem. The state of being in front of G-d unites us together as a tzibbur.

Thursday, August 27, 2020

War Of The People

The Sifri says on the possuk (23:10) כי תצא מחנה. כשתהיה יוצא, הוי יוצא במחנה. The simple explanation is that the entire camp should march together. The Sfas Emes (5636) learns from here a lesson in the מלחמת היצר. When one doesn't view their fight as a personal battle but as part of the general fight of Klal Yisroel, then the individual is supported by all of Klal Yisroel in this battle.

There are seemingly contradictory statements in Chazal if the Yom Hadin is a happy day; as cited in the Tur we wear fancy clothes and eat on Rosh Hashana for we are confident that the din will be good, or is it a scary day as demonstrated by the fact that we don't say hallel and as described in detail in the ונתנה תוקף? Some explain that on the individual level, it is indeed quite a scary day. It is on the level of tzibbur that we are confident that Klal Yisroel will be vindicated. That is why many of the ballei mussar said one should do something that affects others in order to include one's self as part of the tzibbur. Taking such actions will prove that that one is acting as part of the מחנה; fighting the main battle, not just a small skirmish on the side.

There are seemingly contradictory statements in Chazal if the Yom Hadin is a happy day; as cited in the Tur we wear fancy clothes and eat on Rosh Hashana for we are confident that the din will be good, or is it a scary day as demonstrated by the fact that we don't say hallel and as described in detail in the ונתנה תוקף? Some explain that on the individual level, it is indeed quite a scary day. It is on the level of tzibbur that we are confident that Klal Yisroel will be vindicated. That is why many of the ballei mussar said one should do something that affects others in order to include one's self as part of the tzibbur. Taking such actions will prove that that one is acting as part of the מחנה; fighting the main battle, not just a small skirmish on the side.

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Difference Between Man And Animal

In the Mir parsha sheet a couple of weeks ago, Rav Binyamin Cohen quoted from Rav Avrohom Schorr that the avodah of אני לדודי is to give one's אני, their own 'self' to Hashem. By nullifying one's self before Hashem, then it will be ודודי לי. The possuk Koheles (3:19) says ומותר האדם מן הבהמה אין. According to this, we can translate as the advantage of a man over an animal is that a person has the ability to make themselves אין, to turn the אני into אין.

Monday, August 24, 2020

Daas In Kiddushin

ויצאה מביתו והלכה והיתה לאיש אחר

Rashi in Yevamot (19b) says this possuk is the source for how we know that kiddushin must be known with the willingness of the woman - הָלְכָה וְהָיְתָה לְאִישׁ אַחֵר – מדעתה משמע. There is a twofold question on the Rashi. 1. Why do we need a possuk, why is this different from any other kinyan where דעת מקנה is required? 2. Rashi himself in Kiddushin (44a) says that דעת מקנה is the reason that the woman's acquiescence to kiddushin is required?

The Achronim say that the answer lies in the context of the Gemorah in Yevamot. The Gemorah there is discussing if מאמר must be done with the acquiescence of the woman or can even be done against her will. The Gemorah says the Rabbanan hold you need her agreement to go through with מאמר just like her agreement is required for kiddushin. If the only reason that a woman's דעת is required in kiddushin is because of דעת מקנה, that wouldn't make sense to equate to מאמר because she is not the מקנה. Therefore, Rashi understands that the דעת of the woman is an integral part of the maaseh kiddushin.

What difference does it make that the דעת of the woman is required from the possuk?

The Smag (Asseh 48) holds that if someone forces a woman to accept kiddushin, it is not valid. Why would the kiddushin not work, why is it different from any other kinyan where if you force the makneh to do the kinyan it works because under duress they agree to do the sale (תליוהו וזבין)? We see that the Smag holds the possuk is coming to tell us that its not enough with the regular דעת מקנה for kiddushin. The possuk comes to tell us that it's not enough for there to be daas to go through with the kiddushin, but that she must desire for the kiddushin to be done.

What difference does it make that the דעת of the woman is required from the possuk?

The Smag (Asseh 48) holds that if someone forces a woman to accept kiddushin, it is not valid. Why would the kiddushin not work, why is it different from any other kinyan where if you force the makneh to do the kinyan it works because under duress they agree to do the sale (תליוהו וזבין)? We see that the Smag holds the possuk is coming to tell us that its not enough with the regular דעת מקנה for kiddushin. The possuk comes to tell us that it's not enough for there to be daas to go through with the kiddushin, but that she must desire for the kiddushin to be done.

Thursday, August 20, 2020

No Wood

For those learning Rambam at one chapter a day pace, this week we learnt Ch. 6 of the Laws of Foeign Worship and Customs of the Nations. At the end of the chapter he discusses the law of our parsha, לֹֽא־תִטַּ֥ע לְךָ֛ אֲשֵׁרָ֖ה כׇּל־עֵ֑ץ אֵ֗צֶל מִזְבַּ֛ח י״י֥ אֱלֹקיך אשר תעשה לך. The last law in that chapter says אָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת אַכְסַדְרָאוֹת שֶׁל עֵץ בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ כְּדֶרֶךְ שֶׁעוֹשִׂין בַּחֲצֵרוֹת, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהוּא בְּבִנְיָן וְאֵינוֹ עֵץ נָטוּעַ הַרְחָקָה יְתֵרָה הִיא שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (דברים טז כא) "כָּל עֵץ". אֶלָּא כָּל הָאַכְסַדְרָאוֹת וְהַסְּבָכוֹת הַיּוֹצְאוֹת מִן הַכְּתָלִים שֶׁהָיוּ בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ שֶׁל אֶבֶן הָיוּ לֹא שֶׁל עֵץ: The Raavad disagrees א''א לשכת העץ בית היתה, בימה של עץ שעושין למלך בשעת הקהל לשעתה היתה. וכן גזוזטרא שהקיפו בעזרת נשים בשמחת בית השואבה לשעתה היתה:

In Beis Habechirah (1:9) the Rambam says וְאֵין בּוֹנִין בּוֹ עֵץ בּוֹלֵט כְּלָל אֶלָּא אוֹ בַּאֲבָנִים אוֹ בִּלְבֵנִים וְסִיד. וְאֵין עוֹשִׂין אַכְסַדְרוֹת שֶׁל עֵץ בְּכָל הָעֲזָרָה אֶלָּא שֶׁל אֲבָנִים אוֹ לְבֵנִים: The Raavad says א''א והלא לשכת כהן גדול של עץ היתה ובשמחת בית השואבה מקיפין כל העזרה גזוזטרא אלא לא אסרה תורה כל עץ אלא אצל מזבח ה' והיא עזרת כהנים משער ניקנור ולפנים אבל בעזרת נשים ובהר הבית מותר:

The Achronim ask a contradiction in the Raavad for in the first halacha, he seems to allow wooden structures in the Mikdash temporarily but in the second halacha he forbids them in the היכל? Furthermore, in the second halacha he allows wooden structures outside the היכל even permanently, but in the first halacha he allows it only temporarily?

We see from the Rambam that there are two problems with making a wooden structure in the Mikdash. As the name of the Laws indicate and from the possuk that establishes the issue with a אשרה tree, the Rambam derives all wooden structures are prohibited as to distance from idolatry. (This may be a Rabbinic prohibition, see Kesef Mishne.) In Beis Habechira, as the name of the laws indicate, the Rambam isn't mentioning a problem of using wood, rather that the Mikdash must be made from stone or bricks (see there previous halacha,) and therefore wood is excluded. The Rambam isn't telling us a negative of wood, but that there is a positive law to build with stones of bricks. Based upon this maybe we can understand the Raavad. When it comes to the negative of using wood to distance from idolatry, the Raavad holds that if its a structure, not a tree and temporary there is no problem of it leading to idolatry. However, in the Laws of Beis Habechirah he is coming to address the issue of building with materials other than stone/ bricks and there he says that it is a problem only in the עזרת כנהים. (From the sefer קונטרס בעניין נטיעת עץ במקדש pg. 13 -17, https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=57893&st=&pgnum=1&hilite=.)

In Beis Habechirah (1:9) the Rambam says וְאֵין בּוֹנִין בּוֹ עֵץ בּוֹלֵט כְּלָל אֶלָּא אוֹ בַּאֲבָנִים אוֹ בִּלְבֵנִים וְסִיד. וְאֵין עוֹשִׂין אַכְסַדְרוֹת שֶׁל עֵץ בְּכָל הָעֲזָרָה אֶלָּא שֶׁל אֲבָנִים אוֹ לְבֵנִים: The Raavad says א''א והלא לשכת כהן גדול של עץ היתה ובשמחת בית השואבה מקיפין כל העזרה גזוזטרא אלא לא אסרה תורה כל עץ אלא אצל מזבח ה' והיא עזרת כהנים משער ניקנור ולפנים אבל בעזרת נשים ובהר הבית מותר:

The Achronim ask a contradiction in the Raavad for in the first halacha, he seems to allow wooden structures in the Mikdash temporarily but in the second halacha he forbids them in the היכל? Furthermore, in the second halacha he allows wooden structures outside the היכל even permanently, but in the first halacha he allows it only temporarily?

We see from the Rambam that there are two problems with making a wooden structure in the Mikdash. As the name of the Laws indicate and from the possuk that establishes the issue with a אשרה tree, the Rambam derives all wooden structures are prohibited as to distance from idolatry. (This may be a Rabbinic prohibition, see Kesef Mishne.) In Beis Habechira, as the name of the laws indicate, the Rambam isn't mentioning a problem of using wood, rather that the Mikdash must be made from stone or bricks (see there previous halacha,) and therefore wood is excluded. The Rambam isn't telling us a negative of wood, but that there is a positive law to build with stones of bricks. Based upon this maybe we can understand the Raavad. When it comes to the negative of using wood to distance from idolatry, the Raavad holds that if its a structure, not a tree and temporary there is no problem of it leading to idolatry. However, in the Laws of Beis Habechirah he is coming to address the issue of building with materials other than stone/ bricks and there he says that it is a problem only in the עזרת כנהים. (From the sefer קונטרס בעניין נטיעת עץ במקדש pg. 13 -17, https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=57893&st=&pgnum=1&hilite=.)

Two Two's

(עַל־פִּ֣י׀ שְׁנַ֣יִם עֵדִ֗ים א֛וֹ שְׁלֹשָׁ֥ה עֵדִ֖ים יוּמַ֣ת הַמֵּ֑ת (17:6

(19:15) עַל־פִּ֣י׀ שְׁנֵ֣י עֵדִ֗ים א֛וֹ עַל־פִּ֥י שְׁלֹשָֽׁה־עֵדִ֖ים יָק֥וּם דָּבָֽר

Why the change from שנים to שני? Rav Lazer Silver explains based upon the midrash Massey (23:9) that the word שנים means the two are the same type. Based upon this this he says the first possuk which is talking about דיני נפשות where the Gemorah Makkot (6b) says that the witnesses must see the act together, from the same view, then the Torah says שנים. However, the second possuk, dealing with monetary laws, where עדות מיוחדת works, there the Torah says שני for they don't have to see the act together. He says he said this over to the Or Sameach, who approved of the idea. He uses this idea to explain many other ideas as well, see https://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=3001&st=&pgnum=231&hilite=.

(19:15) עַל־פִּ֣י׀ שְׁנֵ֣י עֵדִ֗ים א֛וֹ עַל־פִּ֥י שְׁלֹשָֽׁה־עֵדִ֖ים יָק֥וּם דָּבָֽר

Why the change from שנים to שני? Rav Lazer Silver explains based upon the midrash Massey (23:9) that the word שנים means the two are the same type. Based upon this this he says the first possuk which is talking about דיני נפשות where the Gemorah Makkot (6b) says that the witnesses must see the act together, from the same view, then the Torah says שנים. However, the second possuk, dealing with monetary laws, where עדות מיוחדת works, there the Torah says שני for they don't have to see the act together. He says he said this over to the Or Sameach, who approved of the idea. He uses this idea to explain many other ideas as well, see https://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=3001&st=&pgnum=231&hilite=.

See also here.

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

Killing

The last Even Ezra in the parsha in his final explanation of the final possuk וְאַתָּ֗ה תְּבַעֵ֛ר הַדָּ֥ם הַנָּקִ֖י מִקִּרְבֶּ֑ךָ כִּֽי־תַעֲשֶׂ֥ה הַיָּשָׁ֖ר בְּעֵינֵ֥י י״יֽ says והנכון בעיני, הוא אשר הזכרתי: כי לא ישפך דם נקי בארצך אם תעשה הישר (ראב״ע דברים י״ט:א׳, כ״א:ז׳), כסוד ושכר עבירה עבירה ושכר מצוה מצוה. He reads the possuk as כִּֽי־תַעֲשֶׂ֥ה הַיָּשָׁ֖ר בְּעֵינֵ֥י י״יֽ, by doing the right thing, then, תְּבַעֵ֛ר הַדָּ֥ם הַנָּקִ֖י מִקִּרְבֶּ֑ךָ, blood won't be spilled. That is what he says means שכר עבירה עבירה ושכר מצוה מצוה, by doing a mitzvah it will attract further mitzvot but doing averot allows for mishaps to happen. Why was a man found dead in the vicinity of the city? Because the leaders were lacking in some level. It is the onus of the leaders who's conduct can affect the area around them.

Thursday, August 13, 2020

Pick One

The Otzar Geonim in Kiddushin end of Ch. 1 says a חסיד is one who is super careful with one thing his entire life. It is perfection that makes a chassid, albeit in one area.

In Tanya Epistle 7 the Alter Rebbe says an idea which also focuses on the importance of focusing on one mitzvah. והנה אף שגילוי זה ע"י עסק התורה והמצות הוא שוה לכל נפש מישראל בדרך כלל כי תורה אחת ומשפט א' לכולנו אעפ"כ בדרך פרט אין כל הנפשות או הרוחות והנשמות שוות בענין זה לפי עת וזמן גלגולם ובואם בעוה"ז וכמארז"ל אבוך במאי הוי זהיר טפי א"ל בציצית כו' וכן אין כל הדורות שוין כי כמו שאברי האדם כל אבר יש לו פעולה פרטית ומיוחדת העין לראות והאזן לשמוע כך בכל מצוה מאיר אור פרטי ומיוחד מאור א"ס ב"ה ואף שכל נפש מישראל צריכה לבוא בגלגול לקיים כל תרי"ג מצות מ"מ לא נצרכה אלא להעדפה וזהירות וזריזות יתירה ביתר שאת ויתר עז כפולה ומכופלת למעלה מעלה מזהירות שאר המצות. וזהו שאמר במאי הוי זהיר טפי טפי דייקא. Depending on a person's soul and place in history it may be his/her job to fix up one area specifically. One's barometer of success is how they accomplished there specific goal.

The Gra in beginning of Mishlay Ch. 16 says that a person used to able to go to the prophet who would tell the individual their path in life. After prophesy ended, people can still determine their path through רוח הקודש. The catch is that one can't properly read the code of their רוח הקודש unless they are completely pure of any bad traits. That is the זהיר טפי, it is when one can identify the area of focus most specific to them and perfect that to its extreme. As cited in the Lessons in Tanya, "in the spirit of this teaching, and in view of the fact that the three root letters of the word זהיר (translated above as “careful”) also mean “luminous”, the above-quoted question has been under-stood [by the Mitteler Rebbe] as follows: “As a result of which commandment was your father most luminous?” It is that area that brings out the shine of a person's soul.

This idea is not exactly the same as the Otzar Geonim that puts one's focus on perfecting any one area, but in that finding which area in specific is tied to a person's mission/ soul to bring out. The common denominator though, is that all it takes is one area to really focus on.

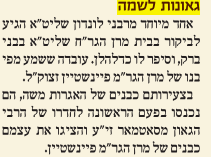

Crazy Story

For those learning the Rambam one ch. a day, the Rambam for 24 Av is Ch. 7 of Talmud Torah. In the יתד האמן מוסף שבת קודש edition for פקודי תשע"ו they have a crazy story printed. The קמ"ל of the story is nice, but how how the story makes sense is something else. (I saw the story copied in one of the comments to Rabbi Y.Y. Jacobson's Rambam shiur and tracked the source of the article via Otzar Hachachma.)

Wednesday, August 12, 2020

Kindness

We learn in the parsha (14:8) that it is a positive

commandment to give charity to a fellow Jew.

The Torah stresses that one should give charity with simcha (ibid

verse 10.) Why is there an

emphasis on simcha by giving charity more than any mitzvah? Why is it that if one gives charity for a

reward he is considered a great tzaddik (Rosh Hashana 4a), he gave for

his own purpose; it’s not a perfect mitzvah?

Why is it specifically by charity that G-d promises to pay back what

one spent and one is even allowed to test G-d to fulfill his promise (see

Malachi chapter 3)? Similarly, the

Gemora tells us in Taanis (9a) that if one gives maaser one will get

rich. Why are these promises made

specially for charity?

The answer lies in the Gemora Yevomos (79a) which describes the nature of Bnei Yisroel as גומלי חסדים. Doing chesed isn't an action one does, but rather is an outgrowth of the nature of Bnei Yisroel (see Or Hatzofon chapter 7.) Doing chesed is a din in the gavra, not in the cheftzah of giving. That is why even if one has an alternative reason for giving charity it still is considered a great deed, for it arouses the natural desire one has to do good for someone else. (See Rashi in Rosh Hashana along these lines for why it is a positive deed only when a Jew gives charity for reward but not for a gentile.)

Tosfos in Bava Metziah (70b) says that if one takes interest from a loan he does not merit to be revived when the dead come alive. Why is there such a severe punishment for taking interest? The Gemorah at the end of Sanhedrin defines a wicked man as one who steals. Why is this the ultimate evil doer? And conversely why is the tzaddik one who gives to others? The explanation may be along the same lines. If one doesn’t give charity it shows he has even corrupted the basic traits of a Jew and therefore doesn’t merit to be resurrected. One who goes even further, to steal is the ultimate evil.

We may add another label of explanation. The whole creation is merely a kindness of G-d, which means one’s whole existence depends upon charity. Therefore, built into the very existence of the whole creation is the need for charity. Based upon this idea, the Bais Halevi in his drashos # 1 explains why by this mitzvah one can test G-d, for charity is what sustains the whole world and when one attaches himself to this trait he merits that G-d will pay him back for upholding the world. Based upon this Beis Halevi we can explain the need for simcha in giving charity as well. Since kindness is what keeps the world running, it behooves one to be in a state of simcha to recognize this fulfillment of the world. When one is fulfilling his potential, one will feel happy as the Maharal often writes. (See the Bais Halevi’s explanation about simcha in a different vein.) The Ekarim volume 3 chapter 33 says that in fact the reward of charity only comes from the simcha infused into it. Now we can understand the severity of taking interest. When one takes interest, it shows a rejection of the kindness of Hashem to give him life and therefore, the person doesn’t merit further life in the time of techias hamasim.

The answer lies in the Gemora Yevomos (79a) which describes the nature of Bnei Yisroel as גומלי חסדים. Doing chesed isn't an action one does, but rather is an outgrowth of the nature of Bnei Yisroel (see Or Hatzofon chapter 7.) Doing chesed is a din in the gavra, not in the cheftzah of giving. That is why even if one has an alternative reason for giving charity it still is considered a great deed, for it arouses the natural desire one has to do good for someone else. (See Rashi in Rosh Hashana along these lines for why it is a positive deed only when a Jew gives charity for reward but not for a gentile.)

Tosfos in Bava Metziah (70b) says that if one takes interest from a loan he does not merit to be revived when the dead come alive. Why is there such a severe punishment for taking interest? The Gemorah at the end of Sanhedrin defines a wicked man as one who steals. Why is this the ultimate evil doer? And conversely why is the tzaddik one who gives to others? The explanation may be along the same lines. If one doesn’t give charity it shows he has even corrupted the basic traits of a Jew and therefore doesn’t merit to be resurrected. One who goes even further, to steal is the ultimate evil.

We may add another label of explanation. The whole creation is merely a kindness of G-d, which means one’s whole existence depends upon charity. Therefore, built into the very existence of the whole creation is the need for charity. Based upon this idea, the Bais Halevi in his drashos # 1 explains why by this mitzvah one can test G-d, for charity is what sustains the whole world and when one attaches himself to this trait he merits that G-d will pay him back for upholding the world. Based upon this Beis Halevi we can explain the need for simcha in giving charity as well. Since kindness is what keeps the world running, it behooves one to be in a state of simcha to recognize this fulfillment of the world. When one is fulfilling his potential, one will feel happy as the Maharal often writes. (See the Bais Halevi’s explanation about simcha in a different vein.) The Ekarim volume 3 chapter 33 says that in fact the reward of charity only comes from the simcha infused into it. Now we can understand the severity of taking interest. When one takes interest, it shows a rejection of the kindness of Hashem to give him life and therefore, the person doesn’t merit further life in the time of techias hamasim.

Tuesday, August 11, 2020

Roots

At the beginning of Ch. 12 the Torah tells us when the Hebrews enter Eretz Yisroel they are to eradicate any trace of idolatry from the land. Rashi says you have to go so far as to לשרש אחריה.

From the context of this possuk it is ruled (see Taz Yoreh Deah 146:12) that this law of לשרש אחריה only applies in Eretz Yisroel. In other words, its a law in settling Eretz Yisroel, not a law in removing avodah zarah.

Many of the sifrei mussar and chassidus use this law as a metaphor for one's own conduct. When one's אל זר has taken root, it is not enough to just remove the bad deeds, one must search for the source of why such conduct is happening to get rid of its very source to guarantee success for the future. As the Gemorah in Shabbos (105b) says כך היא אומנתו של יצר הרע: היום אומר לו עשה כך, ולמחר אומר לו עשה כך, עד שאומר לו עבוד עבודה זרה, והולך ועושה. Its not instantaneous that a person will come to such level of sin, it starts off as a small shoot and grows bigger and bigger.

In light of the previous halacha though, we have an additional twist on this. It is only through the merit of being in Eretz Yisroel that one is able to fully eradicate the אל זר בגופו של אדם. It is the great kedusha of Eretz Yisoel that shines a bright light even in under the dirt of a persons skin and allows one to uproot the roots of evil. This idea is reflected in the Gemorah Arachin (32b) that understands that Moshe couldn't remove the yetzer harah for avodah zarah because he didn't have the merit of Eretz Yisroel, but the later generations, although not as great as Moshe could. It is the merit of the kedusha of Eretz Yisroel that allows one to eradicate avodah zarah (based on Pnenei Harav and Emrei Emes 5670.)

In the ספר זכרון of Rav Hutner in the first section (written by his daughter) it seems he hold that uprooting all forms of avodah zarah is a prerequisite for yishuv Eretz Yisroel :

From the context of this possuk it is ruled (see Taz Yoreh Deah 146:12) that this law of לשרש אחריה only applies in Eretz Yisroel. In other words, its a law in settling Eretz Yisroel, not a law in removing avodah zarah.

Many of the sifrei mussar and chassidus use this law as a metaphor for one's own conduct. When one's אל זר has taken root, it is not enough to just remove the bad deeds, one must search for the source of why such conduct is happening to get rid of its very source to guarantee success for the future. As the Gemorah in Shabbos (105b) says כך היא אומנתו של יצר הרע: היום אומר לו עשה כך, ולמחר אומר לו עשה כך, עד שאומר לו עבוד עבודה זרה, והולך ועושה. Its not instantaneous that a person will come to such level of sin, it starts off as a small shoot and grows bigger and bigger.

In light of the previous halacha though, we have an additional twist on this. It is only through the merit of being in Eretz Yisroel that one is able to fully eradicate the אל זר בגופו של אדם. It is the great kedusha of Eretz Yisoel that shines a bright light even in under the dirt of a persons skin and allows one to uproot the roots of evil. This idea is reflected in the Gemorah Arachin (32b) that understands that Moshe couldn't remove the yetzer harah for avodah zarah because he didn't have the merit of Eretz Yisroel, but the later generations, although not as great as Moshe could. It is the merit of the kedusha of Eretz Yisroel that allows one to eradicate avodah zarah (based on Pnenei Harav and Emrei Emes 5670.)

In the ספר זכרון of Rav Hutner in the first section (written by his daughter) it seems he hold that uprooting all forms of avodah zarah is a prerequisite for yishuv Eretz Yisroel :

Eat Right

This post is a summary of a shiur (my understanding) of a shiur of Rabbi Ezra Schochet on the zoom yarchei kallah for 20 Av.

Rambam Laws of Brachos (1:2) וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ עַל כָּל מַאֲכָל תְּחִלָּה וְאַחַר כָּךְ יֵהָנֶה מִמֶּנּוּ. וַאֲפִלּוּ נִתְכַּוֵּן לֶאֱכל אוֹ לִשְׁתּוֹת כָּל שֶׁהוּא מְבָרֵךְ וְאַחַר כָּךְ יֵהָנֶה. The Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch (167:1) echoes this ruling מִצְוַת עֲשֵׂה מִן הַתּוֹרָה לְבָרֵךְ אֶת ה' אַחַר אֲכִילַת מָזוֹן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר "וְאָכַלְתָּ וְשָׂבָעְתָּ וּבֵרַכְתָּ אֶת ה' וְגוֹ'". וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה. What is noteworthy is why the change in terminology from עַל כָּל מַאֲכָל as the Rambam said, to the words לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה that the Alter Rebbe chooses? Furthermore, the Rambam's words would seem to be more precise for the word אכילה means a כזית as the Alter Rebbe himself writes in 184:2 וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ בִּרְכַּת הַמָּזוֹן עַל כַּזַּיִת, שֶׁהוּא שִׁעוּר אֲכִילָה, אֲבָל פָּחוֹת מִכַּזַּיִת אֵינָהּ נִקְרֵא[ת] אֲכִילָה כְּלָל, and one is obligated to say a beracha before eating even on less than a כזית (as the Rambam and Alter Rebbe 168:7 say)?

To explain why the Alter Rebbe switched from the Rambam's terminology we can say they are going לשיטתם as to what creates the obligation of a beracha. The Rambam holds that anything that is a food obligates one to say a beracha before eating it. Other Rishonim and the ruling of the Alter Rebbe is that one is only obligated for a normal form of eating/drinking. This machlokes is illustrated by a few examples.

1. The Rambam (8:7) based upon Berachos (36b) says הַפִּלְפְּלִין וְהַזַּנְגְּבִיל בִּזְמַן שֶׁהֵן רְטֻבִּין מְבָרֵךְ עֲלֵיהֶן בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה. אֲבָל יְבֵשִׁין אֵין טְעוּנִין בְּרָכָה לֹא לִפְנֵיהֶם וְלֹא לְאַחֲרֵיהֶם מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהֵן תַּבְלִין וְאֵינוֹ אֹכֶל. The Rambam says there is no beracha only because pepper and ginger aren't defined as foods. The Alter Rebbe (202:22) brings the reason of Rashi and other Rishonim that there is no beracha because its not considered fit for consumption, אֲבָל פִּלְפְּלִין יְבֵשִׁים וְזַנְגְּבִיל יָבֵשׁרמג וְכֵן הַצִּפֹּרֶן (שֶׁקּוֹרִין נעגלי"ך), וְכָל כַּיּוֹצֵא בְּאֵלּוּ שֶׁאֵין נֶאֱכָלִים בְּיֹבֶשׁ אֶלָּא עַל יְדֵי תַּעֲרֹבֶת – אֵין מְבָרְכִין עֲלֵיהֶם כְּלוּם כְּשֶׁאוֹכְלָם בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָם, שֶׁאֵין זוֹ אֲכִילָה שֶׁל הֲנָאָה לְבָרֵךְ עָלֶיהָ בִּרְכַּת הַנֶּהֱנִין. Even if they were considered an אוכל, food, there is still no beracha for there is not the normal way to eat these things.

2. The Gemorah (35b) says that drinking olive oil straight is not beneficial for the body. The Alter Rebbe (202:10) holds that there is no beracha said. However, The Rambam (8:2) rules one must say a שהכל. Why, if it is not beneficial at all? The Kesef Mishne says because there is still pleasure in drinking it. That reason is contradicted by the Meiri that says there is no pleasure at all from drinking olive oil. The reason of the Rambam may be explained with a Rabbenu Yonah (28b in Rif cited in Beis Yosef 204:1) that says even though drinking vinegar is not considered drinking to be prohibited on a fast day, since one is obligated for eating on Yom Kippur if they drink an amount of רביעית, therefore, in regard to a beracha as well it is still considered a food. The Bach (204:4) says that is the explanation why the Rambam holds there is a beracha on olive oil. We see again, even though it is not the normal way of eating, since it's defined as an אוכל it is obligated in a beracha. However, the Alter Rebbe goes like the other Rishonim that one is obligated only for eating something that one benefits from. Hence, the Alter Rebbe doesn't say one is obligated to say a beracha on every מאכל like the Rambam, for he holds that being an אוכל doesn't obligate one in a beracha unless it's a normal form of eating, אכילה ושתייה.

That explains why the Alter Rebbe deviates from the language of the Rambam. However, we still need to understand how what he said is true, what happened to the rule of אין אכילה פחותה מכזית? The Rambam at the end of 1:2 says וּמַטְעֶמֶת אֵינָהּ צְרִיכָה בְּרָכָה לֹא לְפָנֶיהָ וְלֹא לְאַחֲרֶיהָ עַד רְבִיעִית: The Kesef Mishne explains because there is no intent to eat - ואפשר לתת סמך לדבר דטעמא משום דכתיב ואכלת וברכת שיהא לו כוונת אכילה משמע. This is מדיוק in the beginning of the Rambam where he says נִתְכַּוֵּן לֶאֱכל אוֹ לִשְׁתּוֹת כָּל שֶׁהוּא, there is כונה to eat. But what does that mean, how can there be כונה to eat if אין אכילה פחותה מכזית? What we see is the rule of אין אכילה פחותה מכזית doesn't mean that is not considered a מעשה אכילה, that it's like eating something that's nor דרכו לאכול. Rather, there is a מעשה אכילה that was done to the food, but it's not considered as if the person ate. With this idea we can also explain some Achronim that hold one is obligated in ברכת המזון even if one didn't eat a כזית in the amount of time of כדי אכילת פרס or the חת"ס holds even for less than a כזית if one is satiated one is obligated. How can this be in the Torah says ואכלת? Because they hold its enough that a מעשה אכילה was done that made the person satiated, one is obligated even though it's not considered as if the person did a מעשה אכילה.

The Minchas Chinuch (430:2) learns that you need an אכילה to be obligated in birchas hamazon so if one ate for example שלא כדרך אכילה there is no obligation. He has a doubt if one ate a כזית normally and the additional amount to add up to כדי שביעה was שלא כדרך אכילה if there is a תורה obligation of birchas hamazon or the entire שביעה must be done through normal eating. The Minchas Chinuch equates שלא כדרך אכילה with a כזית not eaten בכדי אכילת פרס. According to this lomdus, even if you need the entire שביעה to be through אכילה, a כזית not eaten בכדי אכילת פרס, in other words, אכילה פחותה מכזית will be considered a מעשה אכילה to add to the original כזית to make one obligated in birchas hamazon.

Based upon this we understand why it is true what the Alter Rebbe writes לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה because even with less than a כזית it still is a מעשה אכילה of the food.

Rambam Laws of Brachos (1:2) וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ עַל כָּל מַאֲכָל תְּחִלָּה וְאַחַר כָּךְ יֵהָנֶה מִמֶּנּוּ. וַאֲפִלּוּ נִתְכַּוֵּן לֶאֱכל אוֹ לִשְׁתּוֹת כָּל שֶׁהוּא מְבָרֵךְ וְאַחַר כָּךְ יֵהָנֶה. The Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch (167:1) echoes this ruling מִצְוַת עֲשֵׂה מִן הַתּוֹרָה לְבָרֵךְ אֶת ה' אַחַר אֲכִילַת מָזוֹן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר "וְאָכַלְתָּ וְשָׂבָעְתָּ וּבֵרַכְתָּ אֶת ה' וְגוֹ'". וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה. What is noteworthy is why the change in terminology from עַל כָּל מַאֲכָל as the Rambam said, to the words לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה that the Alter Rebbe chooses? Furthermore, the Rambam's words would seem to be more precise for the word אכילה means a כזית as the Alter Rebbe himself writes in 184:2 וּמִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים לְבָרֵךְ בִּרְכַּת הַמָּזוֹן עַל כַּזַּיִת, שֶׁהוּא שִׁעוּר אֲכִילָה, אֲבָל פָּחוֹת מִכַּזַּיִת אֵינָהּ נִקְרֵא[ת] אֲכִילָה כְּלָל, and one is obligated to say a beracha before eating even on less than a כזית (as the Rambam and Alter Rebbe 168:7 say)?

To explain why the Alter Rebbe switched from the Rambam's terminology we can say they are going לשיטתם as to what creates the obligation of a beracha. The Rambam holds that anything that is a food obligates one to say a beracha before eating it. Other Rishonim and the ruling of the Alter Rebbe is that one is only obligated for a normal form of eating/drinking. This machlokes is illustrated by a few examples.

1. The Rambam (8:7) based upon Berachos (36b) says הַפִּלְפְּלִין וְהַזַּנְגְּבִיל בִּזְמַן שֶׁהֵן רְטֻבִּין מְבָרֵךְ עֲלֵיהֶן בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה. אֲבָל יְבֵשִׁין אֵין טְעוּנִין בְּרָכָה לֹא לִפְנֵיהֶם וְלֹא לְאַחֲרֵיהֶם מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהֵן תַּבְלִין וְאֵינוֹ אֹכֶל. The Rambam says there is no beracha only because pepper and ginger aren't defined as foods. The Alter Rebbe (202:22) brings the reason of Rashi and other Rishonim that there is no beracha because its not considered fit for consumption, אֲבָל פִּלְפְּלִין יְבֵשִׁים וְזַנְגְּבִיל יָבֵשׁרמג וְכֵן הַצִּפֹּרֶן (שֶׁקּוֹרִין נעגלי"ך), וְכָל כַּיּוֹצֵא בְּאֵלּוּ שֶׁאֵין נֶאֱכָלִים בְּיֹבֶשׁ אֶלָּא עַל יְדֵי תַּעֲרֹבֶת – אֵין מְבָרְכִין עֲלֵיהֶם כְּלוּם כְּשֶׁאוֹכְלָם בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָם, שֶׁאֵין זוֹ אֲכִילָה שֶׁל הֲנָאָה לְבָרֵךְ עָלֶיהָ בִּרְכַּת הַנֶּהֱנִין. Even if they were considered an אוכל, food, there is still no beracha for there is not the normal way to eat these things.

2. The Gemorah (35b) says that drinking olive oil straight is not beneficial for the body. The Alter Rebbe (202:10) holds that there is no beracha said. However, The Rambam (8:2) rules one must say a שהכל. Why, if it is not beneficial at all? The Kesef Mishne says because there is still pleasure in drinking it. That reason is contradicted by the Meiri that says there is no pleasure at all from drinking olive oil. The reason of the Rambam may be explained with a Rabbenu Yonah (28b in Rif cited in Beis Yosef 204:1) that says even though drinking vinegar is not considered drinking to be prohibited on a fast day, since one is obligated for eating on Yom Kippur if they drink an amount of רביעית, therefore, in regard to a beracha as well it is still considered a food. The Bach (204:4) says that is the explanation why the Rambam holds there is a beracha on olive oil. We see again, even though it is not the normal way of eating, since it's defined as an אוכל it is obligated in a beracha. However, the Alter Rebbe goes like the other Rishonim that one is obligated only for eating something that one benefits from. Hence, the Alter Rebbe doesn't say one is obligated to say a beracha on every מאכל like the Rambam, for he holds that being an אוכל doesn't obligate one in a beracha unless it's a normal form of eating, אכילה ושתייה.

That explains why the Alter Rebbe deviates from the language of the Rambam. However, we still need to understand how what he said is true, what happened to the rule of אין אכילה פחותה מכזית? The Rambam at the end of 1:2 says וּמַטְעֶמֶת אֵינָהּ צְרִיכָה בְּרָכָה לֹא לְפָנֶיהָ וְלֹא לְאַחֲרֶיהָ עַד רְבִיעִית: The Kesef Mishne explains because there is no intent to eat - ואפשר לתת סמך לדבר דטעמא משום דכתיב ואכלת וברכת שיהא לו כוונת אכילה משמע. This is מדיוק in the beginning of the Rambam where he says נִתְכַּוֵּן לֶאֱכל אוֹ לִשְׁתּוֹת כָּל שֶׁהוּא, there is כונה to eat. But what does that mean, how can there be כונה to eat if אין אכילה פחותה מכזית? What we see is the rule of אין אכילה פחותה מכזית doesn't mean that is not considered a מעשה אכילה, that it's like eating something that's nor דרכו לאכול. Rather, there is a מעשה אכילה that was done to the food, but it's not considered as if the person ate. With this idea we can also explain some Achronim that hold one is obligated in ברכת המזון even if one didn't eat a כזית in the amount of time of כדי אכילת פרס or the חת"ס holds even for less than a כזית if one is satiated one is obligated. How can this be in the Torah says ואכלת? Because they hold its enough that a מעשה אכילה was done that made the person satiated, one is obligated even though it's not considered as if the person did a מעשה אכילה.

The Minchas Chinuch (430:2) learns that you need an אכילה to be obligated in birchas hamazon so if one ate for example שלא כדרך אכילה there is no obligation. He has a doubt if one ate a כזית normally and the additional amount to add up to כדי שביעה was שלא כדרך אכילה if there is a תורה obligation of birchas hamazon or the entire שביעה must be done through normal eating. The Minchas Chinuch equates שלא כדרך אכילה with a כזית not eaten בכדי אכילת פרס. According to this lomdus, even if you need the entire שביעה to be through אכילה, a כזית not eaten בכדי אכילת פרס, in other words, אכילה פחותה מכזית will be considered a מעשה אכילה to add to the original כזית to make one obligated in birchas hamazon.

Based upon this we understand why it is true what the Alter Rebbe writes לִפְנֵי כָּל אֲכִילָה וּשְׁתִיָּה because even with less than a כזית it still is a מעשה אכילה of the food.

Thursday, August 6, 2020

Following G-d

וְשָׁ֣מַרְתָּ֔ אֶת־מִצְוֺ֖ת י״י֣ אֱלֹקיךָ לָלֶ֥כֶת בִּדְרָכָ֖יו וּלְיִרְאָ֥ה אֹתֽוֹ- ח:ו

וְעַתָּה֙ יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל מָ֚ה י״י֣ אֱלֹקיךָ מֵעִמָּ֑ךְ כִּ֣י אִם־לְ֠יִרְאָ֠ה אֶת־י״י֨ אֱלֹהֶ֜יךָ לָלֶ֤כֶת בְּכׇל־דְּרָכָיו֙ וּלְאַהֲבָ֣ה אֹת֔ו- י:יב

לְאַהֲבָ֞ה אֶת־י״י֧ אֱלֹקיכֶ֛ם לָלֶ֥כֶת בְּכׇל־דְּרָכָ֖יו וּלְדׇבְקָה־בֽוֹ - יא:כב

Why in the fist possuk does לָלֶ֥כֶת בִּדְרָכָ֖יו precede יראה, in the second one it comes after יראה before אהבה and in the third possuk it comes even after אהבה before לדבקה בו? The Chofetz Chayim (footnote end of intro. to אהבת חסד,) explains that when ever one moves to a higher level it must be preceded by הליכה בדרכיו.

The Rambam (Deos 1:5-6) says וּמְצֻוִּין אָנוּ לָלֶכֶת בַּדְּרָכִים הָאֵלּוּ הַבֵּינוֹנִים וְהֵם הַדְּרָכִים הַטּוֹבִים וְהַיְשָׁרִים שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (דברים כח ט) "וְהָלַכְתָּ בִּדְרָכָיו": כָּךְ לָמְדוּ בְּפֵרוּשׁ מִצְוָה זוֹ. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא חַנּוּן אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה חַנּוּן. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא רַחוּם אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה רַחוּם. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא קָדוֹשׁ אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה קָדוֹשׁ. וְעַל דֶּרֶךְ זוֹ קָרְאוּ הַנְּבִיאִים לָאֵל בְּכָל אוֹתָן הַכִּנּוּיִין אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם וְרַב חֶסֶד צַדִּיק וְיָשָׁר תָּמִים גִּבּוֹר וְחָזָק וְכַיּוֹצֵא בָּהֶן. לְהוֹדִיעַ שֶׁהֵן דְּרָכִים טוֹבִים וִישָׁרִים וְחַיָּב אָדָם לְהַנְהִיג עַצְמוֹ בָּהֶן וּלְהִדַּמּוֹת אֵלָיו כְּפִי כֹּחוֹ: Many commentators on the Rambam point you to Shabbos 133b for the source. However, that is only the basic idea but there אבא שאול derives it from זה קלי ואנוהו. However, the Rambam is understanding that is the commandment of וְהָלַכְתָּ בִּדְרָכָיו as stated in the Sifri in this week's parsha 11:12 on the words לָלֶכֶת בְּכָל-דְּרָכָיו. This is clear from the Rambam in Sefer Hamitzvot #8 where he writes היא שצונו להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת, והוא אמרו "והלכת בדרכיו" (דברים כח, ט). וכבר נכפל זה הצווי ואמר "ללכת בכל דרכיו" (דברים יא, כב) ובא בפירוש (ספרי על דברים, יא כב) "מה הקב"ה נקרא חנון, אף אתה היה חנון; מה הקב"ה נקרא רחום, אף אתה היה רחום; מה הקב"ה נקרא חסיד, אף אתה היה חסיד"

[The Avi Ezri asks how can the Rambam say part of the commandment is to be קדש like Hashem if the Midrash at the beginning of Kedoshim says we can't be קדש like Hashem. The answer seems obvious, the midrash means our kedusha can't equal the level of Hashem's. However, the commandment here is to come as close as we can to Hashem's middos. No one can claim to be as רחום as Hashem, but we are to emulate this as best as possible. I think that is what he answers too.]

How can the Rambam conclude law 5 by saying that the mitzvah leads to being in the middle path if he continues into law 6 saying that the mitzvah is doing actions similar to Hashem?

The son of the Rambam was asked what is the novelty of this mitzvah any more than ואהבת לרעך כמוך? The Lubavitcher Rebbe (Likutay Sichos volume 34 sicha 2 on Ki Savo) says the answer lies in the words of the Rambam "היא שצונו להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת". The mitzvah is to do the actions with intent to follow in the middot of Hashem. In the words of the Rebbe, והיינו ש"והלכת בדרכיו" אינו ציווי הבא לחייב את האדם על ההנהגה (בפועל) ברחמים וחנינה וכיו"ב, כ"א הוא ציווי על ההתדמות — "להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת", שהתנהגותו ברחמים וחנינה כוונתה ומטרתה היא להתדמות לבורא (אלא שבדרך ממילא באה ההנהגה בפועל). ונמצא, שמצוה זו היא מחובת הלבבות, שכוונת האדם בהנהגתו ברחמים וחנינה וכו' צ"ל (לא (רק) משום שהשכל מחייב להתנהג באלו הדרכים משום שהן הנהגות טובות וישרות, אלא) כדי "להדמות בו יתעלה", דמכיון שדרכים אלו הם דרכיו של הקב"ה, לכן הוא מתדמה לו, וכדיוק לשון רז"ל "מה הוא כו' אף אתה כו'", שכל כוונת האדם בהליכה זו היא כדי להדמות לבורא. With this we understand the previous Rambam. Since the mitzvah is to do actions to be like Hashem's actions, therefore it will lead a person to have the perfect balance of the middot like Hashem and be in the middle path.

The Rambam (Deos 1:5-6) says וּמְצֻוִּין אָנוּ לָלֶכֶת בַּדְּרָכִים הָאֵלּוּ הַבֵּינוֹנִים וְהֵם הַדְּרָכִים הַטּוֹבִים וְהַיְשָׁרִים שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (דברים כח ט) "וְהָלַכְתָּ בִּדְרָכָיו": כָּךְ לָמְדוּ בְּפֵרוּשׁ מִצְוָה זוֹ. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא חַנּוּן אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה חַנּוּן. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא רַחוּם אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה רַחוּם. מַה הוּא נִקְרָא קָדוֹשׁ אַף אַתָּה הֱיֵה קָדוֹשׁ. וְעַל דֶּרֶךְ זוֹ קָרְאוּ הַנְּבִיאִים לָאֵל בְּכָל אוֹתָן הַכִּנּוּיִין אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם וְרַב חֶסֶד צַדִּיק וְיָשָׁר תָּמִים גִּבּוֹר וְחָזָק וְכַיּוֹצֵא בָּהֶן. לְהוֹדִיעַ שֶׁהֵן דְּרָכִים טוֹבִים וִישָׁרִים וְחַיָּב אָדָם לְהַנְהִיג עַצְמוֹ בָּהֶן וּלְהִדַּמּוֹת אֵלָיו כְּפִי כֹּחוֹ: Many commentators on the Rambam point you to Shabbos 133b for the source. However, that is only the basic idea but there אבא שאול derives it from זה קלי ואנוהו. However, the Rambam is understanding that is the commandment of וְהָלַכְתָּ בִּדְרָכָיו as stated in the Sifri in this week's parsha 11:12 on the words לָלֶכֶת בְּכָל-דְּרָכָיו. This is clear from the Rambam in Sefer Hamitzvot #8 where he writes היא שצונו להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת, והוא אמרו "והלכת בדרכיו" (דברים כח, ט). וכבר נכפל זה הצווי ואמר "ללכת בכל דרכיו" (דברים יא, כב) ובא בפירוש (ספרי על דברים, יא כב) "מה הקב"ה נקרא חנון, אף אתה היה חנון; מה הקב"ה נקרא רחום, אף אתה היה רחום; מה הקב"ה נקרא חסיד, אף אתה היה חסיד"

[The Avi Ezri asks how can the Rambam say part of the commandment is to be קדש like Hashem if the Midrash at the beginning of Kedoshim says we can't be קדש like Hashem. The answer seems obvious, the midrash means our kedusha can't equal the level of Hashem's. However, the commandment here is to come as close as we can to Hashem's middos. No one can claim to be as רחום as Hashem, but we are to emulate this as best as possible. I think that is what he answers too.]

How can the Rambam conclude law 5 by saying that the mitzvah leads to being in the middle path if he continues into law 6 saying that the mitzvah is doing actions similar to Hashem?

The son of the Rambam was asked what is the novelty of this mitzvah any more than ואהבת לרעך כמוך? The Lubavitcher Rebbe (Likutay Sichos volume 34 sicha 2 on Ki Savo) says the answer lies in the words of the Rambam "היא שצונו להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת". The mitzvah is to do the actions with intent to follow in the middot of Hashem. In the words of the Rebbe, והיינו ש"והלכת בדרכיו" אינו ציווי הבא לחייב את האדם על ההנהגה (בפועל) ברחמים וחנינה וכיו"ב, כ"א הוא ציווי על ההתדמות — "להדמות בו יתעלה כפי היכולת", שהתנהגותו ברחמים וחנינה כוונתה ומטרתה היא להתדמות לבורא (אלא שבדרך ממילא באה ההנהגה בפועל). ונמצא, שמצוה זו היא מחובת הלבבות, שכוונת האדם בהנהגתו ברחמים וחנינה וכו' צ"ל (לא (רק) משום שהשכל מחייב להתנהג באלו הדרכים משום שהן הנהגות טובות וישרות, אלא) כדי "להדמות בו יתעלה", דמכיון שדרכים אלו הם דרכיו של הקב"ה, לכן הוא מתדמה לו, וכדיוק לשון רז"ל "מה הוא כו' אף אתה כו'", שכל כוונת האדם בהליכה זו היא כדי להדמות לבורא. With this we understand the previous Rambam. Since the mitzvah is to do actions to be like Hashem's actions, therefore it will lead a person to have the perfect balance of the middot like Hashem and be in the middle path.

Prayer Without Worship

לְאַהֲבָ֞ה אֶת־י״י֤ אֱלֹֽקיכם וּלְעׇבְד֔וֹ בְּכׇל־לְבַבְכֶ֖ם וּבְכׇל־נַפְשְׁכֶֽם רש"י - עבודה שהיא בלב. בלב – זו תפילה

Obviously, if the point of prayer is עבודה שבלב it is an integral part of prayer. The question is if prayer without intent isn't prayer at all or is just a prayer in an incomplete form. In other words, is the קיום of prayer עבודה שבלב but there is a chaftzah, a maaseh mitzvah of prayer irrespective of עבודה שבלב or without the עבודה שבלב it is not a cheftzah of prayer at all.

The Briskor Rav was asked according to his father's yesod, that one must have the knowledge that he is standing before the King when praying Shemonei Esrai, if many people don't have that intent, does it come out one prayed without a quorum because it is as if they didn't pray as well? The Rav responded that even though a prayer without that intent is incomplete, it still is a chaftzah of prayer (cited in Shoalin V'dorshin of Rav Schlesinger volume 9 siman 4, see there his own answer.) He cited proof from the Keter Rosh of Rav Chayim Volozhiner:

We see although a prayer without concentration is not optimal, it still counts as something. (What is the comparison between korban vs. that of mincha needs an explanation, I don't know why it is that way.)

The halacha is that if one doesn't have concentration in the first beracha of Shemoni Esrai, one must repeat the prayer. The Tur writes that nowadays when proper concentration is often lacking, one should not repeat Shemoni Esrai on account of a lack of concentration. The Beur Halacha beginning of siman 101 points out that from the Chayeh Adam it sounds as if this is true even if one is aware in the middle of their Shemoni Esrai of their lack of intent in Avos. Asks the B.H. how can we tell the person to go ahead and finish their Shemoni Esrai, saying for sure ברכות לבטלה just because repeating Avos may be to no avail? Answers the Steipler (Berachot #27) because although prayer without intent is not עבודה שבלב, it is still a cheftzah of prayer.

There is a lot more on this, תן לחכם וכו.

The halacha is that if one doesn't have concentration in the first beracha of Shemoni Esrai, one must repeat the prayer. The Tur writes that nowadays when proper concentration is often lacking, one should not repeat Shemoni Esrai on account of a lack of concentration. The Beur Halacha beginning of siman 101 points out that from the Chayeh Adam it sounds as if this is true even if one is aware in the middle of their Shemoni Esrai of their lack of intent in Avos. Asks the B.H. how can we tell the person to go ahead and finish their Shemoni Esrai, saying for sure ברכות לבטלה just because repeating Avos may be to no avail? Answers the Steipler (Berachot #27) because although prayer without intent is not עבודה שבלב, it is still a cheftzah of prayer.

There is a lot more on this, תן לחכם וכו.

Tuesday, August 4, 2020

Your Son Is A Gadol

The Rambam Daos (3:3) המנהיג עצמו על פי הרפואה אם שם על לבו שיהיה כל גופו ואבריו שלמים בלבד ושיהיו לו בנים עושין מלאכתו ועמלין לצורכו אין זו דרך טובה אלא ישים על לבו שיהא גופו שלם וחזק כדי שתהיה נפשו ישרה לדעת את ה' שאי אפשר שיבין וישתכל בחכמות והוא רעב וחולה או אחד מאיבריו כואב וישים על לבו שיהיה לו בן אולי יהיה חכם וגדול בישראל נמצא המהלך בדרך זו כל ימיו עובד את ה' תמיד

The Sefer הוגה דעות brings that we see one must raise their children to give them the capability to be giants in Torah.

The Sefer הוגה דעות brings that we see one must raise their children to give them the capability to be giants in Torah.

Guard Your Soul

רק השמר לך ושמר נפשך מאד פן תשכח את הדברים אשר ראו עיניך

ונשמרתם מאד לנפשתיכם כי לא ראיתם כל תמונה

The Gemorah in Berachos (32b) brings a story תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: מַעֲשֶׂה בְּחָסִיד אֶחָד שֶׁהָיָה מִתְפַּלֵּל בַּדֶּרֶךְ. בָּא הֶגְמוֹן אֶחָד וְנָתַן לוֹ שָׁלוֹם, וְלֹא הֶחְזִיר לוֹ שָׁלוֹם. הִמְתִּין לוֹ עַד שֶׁסִּייֵּם תְּפִלָּתוֹ. לְאַחַר שֶׁסִּייֵּם תְּפִלָּתוֹ, אָמַר לוֹ: רֵיקָא, וַהֲלֹא כָּתוּב בְּתוֹרַתְכֶם ״רַק הִשָּׁמֶר לְךָ וּשְׁמֹר נַפְשְׁךָ״, וּכְתִיב ״וְנִשְׁמַרְתֶּם מְאֹד לְנַפְשֹׁתֵיכֶם״. כְּשֶׁנָּתַתִּי לְךָ שָׁלוֹם לָמָּה לֹא הֶחְזַרְתָּ לִי שָׁלוֹם? אִם הָיִיתִי חוֹתֵךְ רֹאשְׁךָ בְּסַיִיף, מִי הָיָה תּוֹבֵעַ אֶת דָּמְךָ מִיָּדִי?! This is the source for the Rambam (Shmeris Hanefesh 11:4) says וכן כל מכשול שיש בו סכנת נפשות מצות עשה להסירו ולהשמר ממנו ולהזהר בדבר יפה יפה. שנאמר השמר לך ושמור נפשך. ואם לא הסיר והניח המכשולות המביאין לידי סכנה ביטל מצות עשה ועבר בלא תשים דמים. There are numerous questions on this, see Maharsha in Berachos and Minchas Chinuch on the mitzvah of making a מעקה. However besides all that , the simple read of the possuk is referring to a spiritual danger.The Chofetz Chayim derives from here a lesson; when one's being careful to avoid physical harm, one must also avaid spiritual harm:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)